The Origin of Decentralized Autonomous Networks

Satoshi Nakamoto believed that repeated violations of public trust by centralized financial institutions necessitated the creation of a trustless and decentralized peer-to-peer digital currency based on blockchain technology. By early 2009, in the midst of a global financial crisis, many others had echoed Satoshi’s sentiment as public faith in financial institutions was at its nadir. The distributed yet collaborative community of blockchain enthusiasts that began to materialize was reflected in the trustless and decentralized nature of blockchain technology itself. As individuals, however, they lacked the power to challenge traditional financial institutions.

After smart contracts were developed by Ethereum and Proof-of-Stake was successfully implemented by Peercoin, the organization of blockchain enthusiasts into large, distributed groups with shared financial goals became feasible. The bylaws of a decentralized organization could be written into transparent, verifiable, and publicly auditable smart contracts. Members could stake their tokens in exchange for the voting power to make critical decisions about the management of their organization including its partnerships, technical upgrades, and treasury allocations. Even the bylaws could be changed if a consensus was reached. This collectively governed organization of stakeholders, whose operations are wholly owned and managed by its members in the absence of a central authority, is known as a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO).

The Growth and Legal Recognition of DAOs

While some consider Bitcoin to be the first DAO due to the governance mechanism of its mining network, Dash is the first modern DAO, launched in 2014, that provided a governance mechanism for its stakeholders and allowed them to vote on proposals that decided the future of the organization. BitShares was launched that same year as an e-commerce platform that connected merchants to customers in the absence of a central authority.

Unfortunately, the most widely-recognized DAO was an Ethereum-based organization simply called The DAO that raised $150 million from investors in 2016 before suffering from an exploit in its code that drained one third of its treasury and ended the project a mere 5 months after launch. The funds were returned, but only at the cost of a controversial hard-fork of Ethereum, which resulted in the creation of Ethereum Classic. While the attack on The DAO sent shockwaves through the blockchain community and undermined the legitimacy of DAOs for a time, development has continued and DAOs are now considered a legal entity in the state of Wyoming with more states likely to follow.

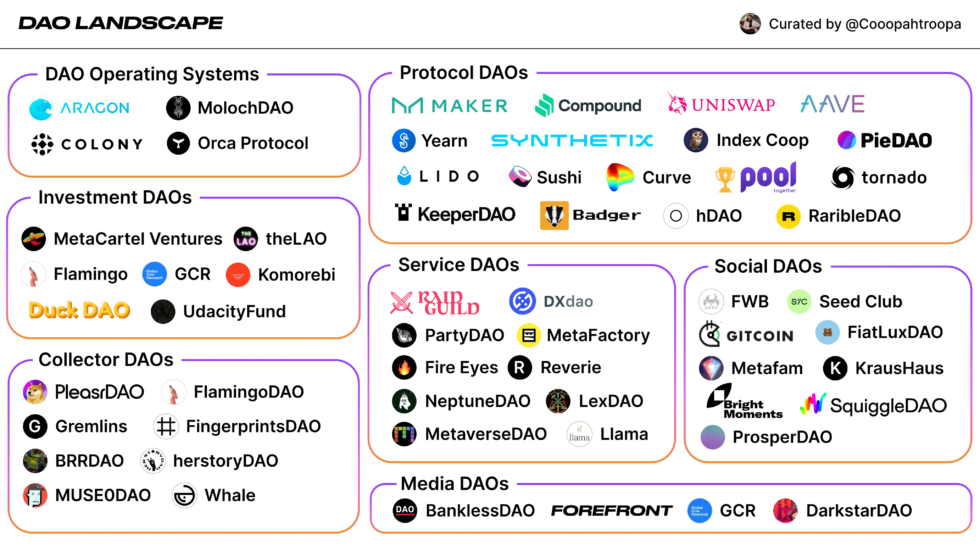

Continued innovation of DAOs and their growing recognition as legitimate financial institutions has led to their adoption by nearly every financial sector. For example, MakerDAO provides collateral-backed loans against cryptocurrency and real-world assets, JennyDAO issues fractional shares of NFTs, Nexus Mutual offers insurance, Raid Guild contributes to the gig economy, and Endaoment pools charitable contributions that are distributed by their stakeholders. A partial map of the DAO ecosystem is illustrated below.

The Advantages and Disadvantages of DAOs

The most compelling advantage of DAOs is their elimination of the principle-agent dilemma. In traditional finance, there is an inherent conflict in priorities between the principle, who invests in a fund, and the agent, who manages the fund. For example, a trader may take on excessive risk at the expense of their investors by investing in volatile assets or using highly leveraged positions with the goal of securing a large year-end bonus. Here, the agent’s goal of a bonus is in potential conflict with the principle’s goal of profiting from their investment. In a DAO, however, each member contributes to the purchasing and management of an asset. Therefore, the stakeholders of a DAO are both the agent and the principle whose priorities are aligned.

DAOs also benefit a stakeholder through greater 1) efficiency in business operations 2) transparency in rules and operations and 3) autonomy in how their assets are managed.

Efficiency: The lack of hierarchical structures inherent in traditional finance eliminates bureaucratic inefficiencies. In a DAO, decisions are reached by community consensus after a quorum is reached.

Transparency: The rules of a DAO are embedded in smart contracts that can be publicly audited. Contract details and transactions are permanently recorded on the blockchain.

Autonomy: A stakeholder has complete ownership of their investments. They can also participate in a project from inception to exit at their own discretion without facing complex regulatory hurdles.

The positive attributes of a DAO can unfortunately work against the organization when things go wrong. For example, transparent code gives hackers the opportunity to simulate an attack on a virtual machine before an attack is launched on the actual network. In the case of The DAO, a vulnerability in the code was publicly reported and the community was called to a vote after a patch had been developed. However, the hack occurred before the voting could be completed, resulting in a loss of 11.5 million Ether. The decentralization of authority means that no one is held accountable for monetary losses or legal action taken against the DAO. The involvement of non-experts in the decision-making process leaves the DAO particularly vulnerable to lawsuits, which may be filed across multiple jurisdictions because of the decentralized nature of the DAO. For example, a DAO may be sued if a stakeholder contributes to a private equity fund without being an accredited investor.

The Sponsored DAO

A sponsored DAO (SDAO) is a theoretical organization that is collectively owned by its members but managed by an accredited institution (e.g. a bank or investment firm). The governing institution is responsible for specifying the lending criteria for borrowers, maintaining KYC/AML records for all stakeholders, and providing backstop liquidity for tokenized assets that are locked into Digital Special Purpose Vehicles (DSPVs) to securitize these assets and create liquidity pools for investors.

DSPVs can be multi-tranche, giving investors the choice between a lower risk investment with stable returns, and a higher risk investment with variable returns. This model is being implemented by Centrifuge, which recently integrated its Tinlake marketplace with MakerDAO to provide loans that are backed by real-world assets. Tokenized assets may also be integrated with financial oracles that aggregate real-time performance and valuation data. Sponsoring organizations with access to advanced software and financial experts who can interpret this data will help stakeholders make informed decisions about their investments.

How Accumulate Enables the Creation of an SDAO

Financial oracles generate a large volume of data that must be synced to the tokenized asset and credentialed by institutions with legal authority. The Accumulate protocol can process transactions with low cost, high throughput, and minimal storage requirements due to its efficient data structure. Accumulate can also integrate with traditional tech stacks, meaning that financial institutions can use the Accumulate network to manage assets without having to adapt their technology.

The Accumulate protocol’s hierarchical identity and key structure enables asset management with greater flexibility and less granularity than traditional DAOs. Attestations given to stakeholders and managed by sponsoring institutions allow stakeholders to invest in different assets depending on their status (e.g. accredited investor). Complex operations like subdividing and selling a mortgaged property are possible on the Accumulate network due to its powerful identity capabilities that allow multiple key holders with different priority levels to create signature groups that can be managed over time.

To understand how this identity framework may be applied in the real-world, imagine a sponsoring bank with a senior Vice President who is in charge of agents who manage investments in the SDAO. The bank may provide the VP with an attestation that authorizes the VP to issue their own attestations to agents who in turn can provide attestations to individual stakeholders. Each entity has an identity on the Accumulate network that is capable of assigning and revoking authority to those who are lower on the identity hierarchy. The bank can revoke the VP’s authority just as the VP can revoke an agent’s authority, and an agent can remove a stakeholder’s authority if they lose accredited investor status.

Hierarchical key sets in Accumulate are also useful for managing high value tokens. Consider a non-fungible token (NFT) that represents a bundle of real-estate valued at $100 million. In traditional blockchains, the loss or theft of a key can result in an irreversible loss of the NFT. Multisignature authorization (Multisig) can provide an additional layer of security at the cost of flexibility. For example, adding or selling a piece of real-estate might take days given time locks in the Multisig contract and delays in acquiring the threshold number of signatures. Accumulate allows administrative keys to be maintained in cold storage while enabling routine operations with lower priority keys.

Conclusion

Decentralized autonomous organizations are the natural byproduct of collective frustration with financial institutions by a decentralized collective of blockchain enthusiasts. Over time, however, DAOs began to associate with these same institutions by outsourcing certain operations, such as KYC/AML, to qualified organizations. With the implementation of an SDAO, stakeholders will be able to minimize their legal exposure, make better informed decisions, and participate in more complex financial activities while maintaining a high degree of autonomy. This type of organization is uniquely possible on the Accumulate network due to its powerful identity and key management capabilities.

0 Comments